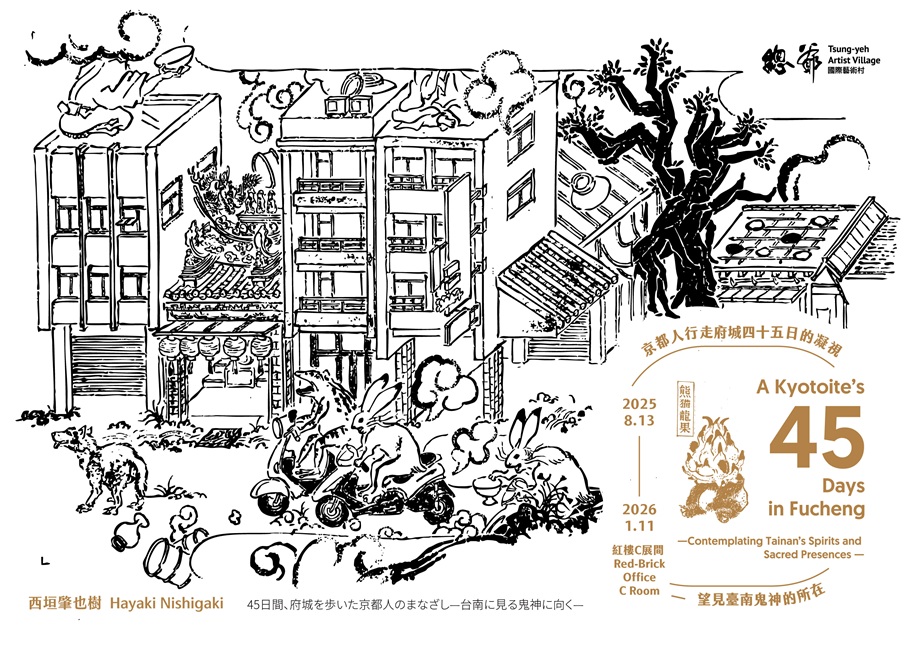

【總爺國際藝術駐村計畫】《京都人行走府城四十五日的凝視——望見臺南鬼神的所在》西垣肇也樹駐村成果展

08.13 (三)

01.11 (日)

【總爺國際藝術駐村計畫】《京都人行走府城四十五日的凝視——望見臺南鬼神的所在》西垣肇也樹駐村成果展

│京都人行走府城四十五日的凝視——望見臺南鬼神的所在

│A Kyotoite’s Gaze After 45 Days in Fucheng— Contemplating the Sacred and the Unseen in Tainan —

│西垣肇也樹 Hayaki Nishigaki

➤展覽介紹

自古以來,蛇與龍 被視為掌管河川與水域的存在,亦象徵著王權與自然而受到敬畏。在中國,龍比較普遍;而在臺南,曾文溪被稱為「青瞑蛇」,如同一條不受控暴走的盲目巨蛇,不時地引發洪患與改變河道。然而在日治時期,隨著八田與一興建烏山頭水庫與嘉南大圳,土壤變得肥沃;曾文水庫與堤防整備,河川終於有效地被人們管理。自此,自然(神)與人類之間的關係也出現了極大的改變。

與此同時,臺灣近代出現一些女鬼的傳說。因被賣身,守節不從被殺的陳守娘,還有遭受背叛,最後在林投樹下自盡的林投姐 ,這些女性因強烈怨懟而形成了怪談。她們不僅令人畏懼,也乘載著眾人的祈念,最終成為鬼神被祀奉。她們的故事都顯示男性的負心,社會讓女人無法由正常的管道申訴,迫使她們訴諸報復以伸張正義。

像這樣的例子,即便不是聖人,無名的凡人也可能被視為鬼神,成為人們信仰的對象。

藝術家試著將這些女鬼的故事與日本的「哥吉拉」對照探討。因核能實驗而產出的哥吉拉,是因爲人類的科學與慾望失控所誕生,亦可稱為現代版「神」之存在。從鎮定鬼神的信仰,與人們顧守核能反應爐失控的態度來看,皆可感受到相同的「畏懼」與「尊敬」。

昔日的我們,敬畏著如同大蛇與龍的大自然,隨著時代變遷,我們開始從人類所創造的事物――技術、報復、冤屈、慾望――看見了鬼神的存在。然而,如丹娜絲颱風般的天災仍時時重創人類,不禁使人聯想到所謂的「龍之暴動」。

如今身處臺南的他,將壯麗的大自然、水利技術、人類文明的流轉、女鬼與哥吉拉一一重疊,試著描繪出一幅屬於當代的鳥瞰圖,呈現這片多重交錯的風景。

自古以來,蛇與龍 被視為掌管河川與水域的存在,亦象徵著王權與自然而受到敬畏。在中國,龍比較普遍;而在臺南,曾文溪被稱為「青瞑蛇」,如同一條不受控暴走的盲目巨蛇,不時地引發洪患與改變河道。然而在日治時期,隨著八田與一興建烏山頭水庫與嘉南大圳,土壤變得肥沃;曾文水庫與堤防整備,河川終於有效地被人們管理。自此,自然(神)與人類之間的關係也出現了極大的改變。

與此同時,臺灣近代出現一些女鬼的傳說。因被賣身,守節不從被殺的陳守娘,還有遭受背叛,最後在林投樹下自盡的林投姐 ,這些女性因強烈怨懟而形成了怪談。她們不僅令人畏懼,也乘載著眾人的祈念,最終成為鬼神被祀奉。她們的故事都顯示男性的負心,社會讓女人無法由正常的管道申訴,迫使她們訴諸報復以伸張正義。

像這樣的例子,即便不是聖人,無名的凡人也可能被視為鬼神,成為人們信仰的對象。

藝術家試著將這些女鬼的故事與日本的「哥吉拉」對照探討。因核能實驗而產出的哥吉拉,是因爲人類的科學與慾望失控所誕生,亦可稱為現代版「神」之存在。從鎮定鬼神的信仰,與人們顧守核能反應爐失控的態度來看,皆可感受到相同的「畏懼」與「尊敬」。

昔日的我們,敬畏著如同大蛇與龍的大自然,隨著時代變遷,我們開始從人類所創造的事物――技術、報復、冤屈、慾望――看見了鬼神的存在。然而,如丹娜絲颱風般的天災仍時時重創人類,不禁使人聯想到所謂的「龍之暴動」。

如今身處臺南的他,將壯麗的大自然、水利技術、人類文明的流轉、女鬼與哥吉拉一一重疊,試著描繪出一幅屬於當代的鳥瞰圖,呈現這片多重交錯的風景。

Since time immemorial, serpents and dragons have been revered as sacred beings pre-siding over rivers and waterways—symbols of both royal authority and the untamed power of nature. In China, dragons are more commonly seen; while in Tainan, the Zengwen River was once called the “Qing-Ming Snake,” a blind, rampaging serpent whose unpredictable movements brought floods and reshaped waterways time and again.

This ancient relationship between humans and nature began to shift during the Japanese colonial period. With the construction of the Wushantou Reservoir and the Chianan Irri-gation System by engineer Yoichi Hatta, the land became fertile. The later completion of the Zengwen Reservoir and the reinforcement of flood-control embankments allowed the river to be effectively governed. In this transformation, the bond between nature—as divine presence—and humankind was profoundly reconfigured.

Meanwhile, Taiwan’s modern era gave rise to a series of female ghost legends. Among them are figures like Chen Shou-niang (陳守娘), who was sold and later exe-cuted for resisting sexual coercion, and Sister Lin-Tou (Lin-Tou Jie, 林投姐), who end-ed her life beneath a screw pine tree after enduring betrayal. Their unresolved anguish took shape as supernatural presences—stories born of sorrow, yet infused with awe. Over time, they came to be venerated as ghost-deities (guishen, 鬼神), gathering both fear and prayer from those who remembered them.

Their stories often reveal the heartbreak caused by male betrayal, and the lack of chan-nels for women to seek justice within society. Many were driven to vengeance as a way of claiming moral or cosmic redress.

Even in cases like this, those who are neither saints nor nobility—ordinary, nameless individuals—may become objects of worship. Their pain, unheeded in life, is trans-formed into spiritual presence in death.

I find echoes of these ghostly women in Japan’s Godzilla—a creature born of nuclear experimentation, a manifestation of modern humanity’s unbridled science and desire. In many ways, Godzilla can be seen as a contemporary god: terrifying, untouchable, and born from our own hands.

The rituals meant to appease the ghost-deities and the anxious vigilance with which people watch over unstable nuclear reactors, both reflect a similar emotional stance—one shaped by awe and reverence toward forces beyond human control.

Once, we trembled before the great serpents and dragons that embodied nature itself. But over time, our gaze has shifted. Today, we glimpse ghost-deities not only in the wild, but also in the things we have created—in technology, in revenge, in injustice, and in desire.

Yet nature still reminds us of its presence. Disasters like Typhoon Danas continue to strike with overwhelming force, conjuring the image of a dragon in fury—proof that the ancient wildness has never truly disappeared.

Now, standing in Tainan, I find myself layering together vast nature, hydraulic engi-neering, the ebb and flow of human civilization, the presence of female ghosts, and the shadow of Godzilla. Through this convergence, I attempt to draw a contemporary aerial map—one that traces the entangled contours of this intricate landscape.